... the thoughts of a turtle are turtles ...

If you never kept a turtle as a pet, I don’t recommend it. First and most seriously they are difficult to care for unless you know what you are doing, and largely for this very reason are prone to die a young and untimely death. Another problem is that they often get sick and tired of that terrarium you’ve locked them up in and start scratching nonstop on the walls trying to get out. You wonder if they are just bored or nervous, or in need of a larger living room. The constant scraping noise can be so irritating you could scream and throw a lamp across the room.

But this blog is more about us humans than it is about the challenges of turtle care. Do you ever even imagine that effort itself could, in some circumstances, prove to be an insurmountable impediment to progress? Counterintuitive insight at its best!

I’m convinced the metaphoric image of the turtle in the bronze basin will be subject of this blog. At least I will try. Wait for the future, as I suppose we have all been doing, and we’ll get there. My primary aim is to persuade you how crucial it is for us to better know in practical terms what futile efforts entail. If I can convince you of this my struggles will not have been in vain. At long last I will be able to give it a rest.*

(*I suppose my further subterranean aim would be to show that there are connections such as this to be seen in the pre-Mongol era between the Bon, Zhijé and Nyingma schools.)

In a selection from one of the primary texts of the early Zhijé tradition containing words of Padampa we once translated as Padampa’s Animal Kingdom, we find these words:

17. Unable to go anywhere, the turtle in the bronze basin tires itself out.

འགྲོ་བར་མྱི་ནུས་མཁར་ཞོང་ནང་གི་རུལ་རྦལ་ཚི་ཆད་འགྱུར་།། — ZC vol. 1, p. 219.4.

The metaphor of the turtle in the bronze basin occurs at least twice in the Padampa Tanjur texts, but curiously in them the emphasis seems to be on how much the turtle in the bronze basin enjoys basking in the sun, and not on how thoroughly trapped it is. The commentarial text explains Padampa’s precept and, as it often does, gives it an unexpected spin:

17. “Unable to go...” — If you place a turtle in a bronze basin, it tries to climb out, but at the very first step it loses its footing. Likewise, no matter how high or low something may appear, the mind never moves from its empty nature. It falls back on it.

འགྲོ་མྱི་ནུས་ཞེས་པ་ནི་། འཁར་གཞོང་དུ་རུ་རྦལ་བཅུག་ན་ཕྱིར་འཛེགས་ཀྱང་ཡང་དང་པོའི་ཤུལ་དུ་འདྲེད་ནས་འོང་། དེ་བཞིན་དུ་འཐོའ་དམན་ཇི་ལྟར་སྣང་ཡང་སེམས་ངོ་བོ་སྟོང་པ་ལས་འགྱུར་བ་མྱེད་དེ་། དེ་ཐོག་ཏུ་འབབས་གསུང་། — ZC, vol. 1, p. 426.

(*For the bibliographical details, refer to the recent blogs on the Four Caches).

At first glance I had thought it might be a Zhijé text, seeing the words meaning ‘From the mouth of Dampa’ (dam pa’i zhal nas) that seemed to suggest it, although it soon turned out to be an illusion. I tried searching in BDRC, and found no matches to the phrases I was trying to check. However, I tried again and found this parallel to the Khyunglung fragment in vol. 121 of The Much Expanded Version of the Oral Scriptures of the Earlier Translations (Snga-’gyur Bka’-ma Shin-tu Rgyas-pa, W1PD100944). In this instance BDRC e-text provides us with no page correspondences (and this is my good excuse for not providing page numbers), although this volume does seem to be a commentary on the Eighty Precepts (Zhal-gdams Brgyad-cu-pa) of Zurchung:

le'u bdun pa / gdams pa bcu gsum gyi gdams ngag lag len gdams pa ni / gdams pa bcu gsum la / bsgrub pa'i brtson 'grus kyi lcag tu bdag gzhan gyi 'chi ba la brtag / nam mchi nges pa med pas tshe 'di yi bya bzhag thams cad bor thongs / gus pa khyad par can skye bar 'dod pas bla ma'i phyi nang gi yon tan la brtag / skyon rtog spongs / skyon du snang ba de rang snang ma dag pas lan / spyod pa kun dang mthun par 'dod pas gzhan gyi rtsol ba mi dgag / theg pa thams cad rang sa bden pas chos dang grub mtha'i kha 'dzin che / bla ma'i thugs zin pa mi 'gyur bar bya ba'i phyir nyams su len pa drag tu bya / yon tan ma lus pa rang la 'ong / dngos grub myur du thob par 'dod na sdom pa dam tshig ma nyams par bsrung / bsrung mtshams mtha' dag mi dge bcu dang dug lnga rang mtshan la slong bar 'du / chu bo bzhin bcad par.*

(*Compare this to the Khyunglung fragment starting at its folio 3 recto, line 7, and you will see despite all the variant readings that they are the same text all the same.)

I see, too, that Khyunglung, p. 144, line 5 ff. (or fol. 3 verso, line 5) corresponds to section 13 in the English of Zurchungpa’s Testament (its pp. 94-95). The ordering of sections doesn’t seem to be the same in the Khyunglung when compared to later editions of the “same” text. This indicates that a close textual study would be in order. At the moment I cannot safely argue for dependence of one text on the other. A comparative text edition ought to be made, perhaps you would like to give it a try?

In any case, as you may have suspected by now the Zurchung Eighty does contain the turtle in the bronze basin metaphor even if it may not look like it in the English:

“Cut the stream of the arising of dualistic thoughts and the following after them, taking the example of a tortoise placed on a silver platter.” (no. 28 on p. 164, see also pp. 292, 346)

I find the Tibetan of it in my physical print volume of the text entitled

Zur-chung Shes-rab-grags-pa'i Gdams-pa Brgyad-cu-pa, Pema Thinley, Sikkim National Press (Gangtok 1999), a booklet in 64 pages not listed in BDRC, at p. 26:

རུས་སྦལ་མཁར་གཞོང་དུ་བཅུག་པའི་དཔེས་མཚོན་ནས། མཚན་མའི་འབྱུང་འཇུག་རྒྱུན་བཅད།

I go to the trouble to give the Tibetan to convince Tibetan readers that it really does speak of the turtle stuck in a bronze basin, and that the published English translation, as wonderful as it is, is in my estimation slightly off on this particular point. I myself originally wanted to translate brass basin, liking the sound of it, but really, it’s a superior type of brass alloy, and that means some more expensive kind of bronze or bell metal.

To complicate matters necessarily, we find the turtle in the bronze basin in a Bon Dzogchen text of the pre-Mongol era that would need to be brought into a fuller and more adequate discussion. The Bon text I have in mind is Seeing Awareness in its Nakedness (Rig-pa Gcer Mthong), IsIAO Tucci text no. 528, section DA, folio 2 verso, line 6. I would give a quotation, but I no longer have a access to the Tucci manuscript and would need to search it out in one of the published editions of the massive cycle that contains it.

This section DA, according to the published catalog

Elena De Rossi Filibeck, Catalogue of the Tucci Tibetan Fund in the Library of the IsIAO, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (Rome 2003), vol. 2, p. 296.

ought to be a 7-folio manuscript with the title Bsnyan-rgyud Gsal-bar Byed-pa'i Gsal-byed. I had thought I might have made a photo of the page, but no, to find it again I would have to fly back to Rome. That hardly seems likely to happen today. Anyway, I believe it ought to be locatable in a different published version of the cycle, so let me go over to BDRC and see what I can come up with.

Well, I went there and came up with nothing, because the volume I’ll describe in a flash isn’t listed there:

Snyan-rgyud Gcer-Mthong, “Bonpo oral transmission precepts granted by Srid-pa-rgyal-mo to Bon-zhig Khyung-nag, reproduced from rare manuscript from Bsam-gling Monastery in Dol po,” Tibetan Bonpo Monastic Centre (Dolanji 1972).

That’s a pity that BDRC didn’t scan it.* You might think I’m lucky to have a IASWR microfiche set that ought to include it, but then I don’t have any fiche reader available to me right now.

(*Or didn’t scan it yet. Those 1960's-1980's Bon publications from India haven’t mostly been posted online, although they might be in the near future.)

Okay, now I think I can find it. As you may know the catalog of the Bon Katen goes with an index volume,

Samten G. Karmay and Yasuhiko Nagano, eds., A Catalogue of the New Collection of Bonpo Katen Texts (Bon Studies 4), Senri Ethnological Reports series no. 24, National Museum of Ethnology (Osaka 2001).

and it locates the cycle of Seeing Awareness in Its Nakedness in volume 133 of the 300 (plus) volume set. That set is locatable with the title “Bon-gyi Bka’-brten” in BDRC as no. W30498, and its volume 133 is indeed scanned and made available there. What we find when we view the scans of vol. 133 is what looks very much like a photocopy of the 1972 publication listed above (absent only the added title page, and the Table of Contents that could have come in useful). A telltale sign is the Old Delhi style of the added Arabic numerals.* So we go back to the 1,692-page Osaka catalog and run through the titles it lists for vol. 133. Even if it isn’t exactly Gsal-bar Byed-pa’i Gsal-byed, we do see that part 15 (pp. 265-278, or 7 folios in length) has the title Snyan-rgyud Gsal-byed, which seems promising enough to have a look.

(*How can I tell? It kind of looks like the numbers were applied with a rubber stamp.)

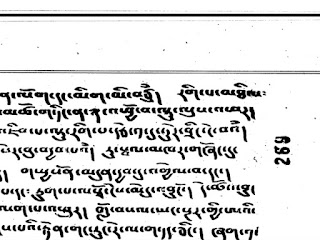

Could you hear the scratching? A few hours have passed, and I wish I could tell you that all those efforts had no result whatsoever. That would have made my point for me. But no, there it is on p. 269, line 4: ru[s] sbal mkhar gzhong du, or, turtle in a bronze basin. Have a look:

Of course, now we have the difficult task of understanding it in its special context, as part of a system of Dzogchen precepts. We’ve barely scratched the surface... Or... Perhaps we’ve scratched enough for one day. It may be time to give it a rest.

|

Originally from Buzzfeed, I linked it from here: As you see this is a plastic, and not a bronze basin, or the outcome would be different. |

•

A poem by Emily Dickinson has more of the “well turtle” or turtle-in-a-well in it, even if the turtle is disguised as a mole. The piece as a whole is usually taken to be about 19th-century disenchantment or, to put it in different words, our declining perception of the sacred dimensions of our existence.

1228

So much of Heaven has gone from Earth

That there must be a Heaven

If only to enclose the Saints

To Affidavit given.

The Missionary to the Mole

Must prove there is a Sky

Location doubtless he would plead

But what excuse have I?

Too much of Proof affronts Belief

The Turtle will not try

Unless you leave him - then return

And he has hauled away.

I’m fascinated how in the verse on the mole in a hole we easily perceive the well known Indic metaphor of the well turtle (he finds difficulty believing what he is told about the wider world beyond his ken), while the very next verse seems to have our turtle escaping from an unspecified container. Could she have gotten something from Emerson? But for her, okay, it is quite a different idea, the turtle only tries to get away when you aren’t looking. Then just disappears.

•

In John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, a turtle appears to be a symbol of the family’s struggle for freedom, but here the turtle is in a shirt pocket (or is he crossing the highway?) and not in any basin.

•